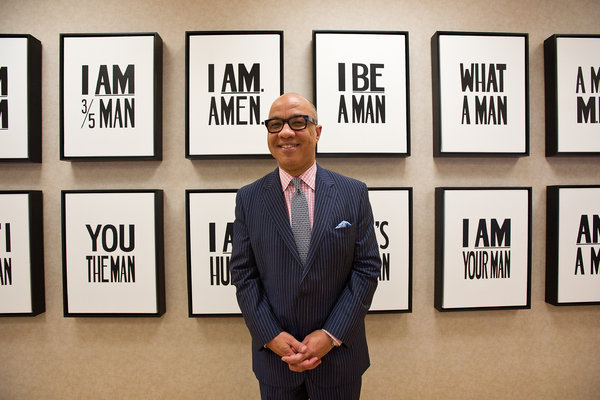

Darren Walker (pictured above) was born in a charity hospital in Lafayette, La., and grew up in the 1960s in a single-parent household in rural Texas, where his mother worked as a nurse’s aide and he was enrolled in one of the first Head Start programs. He went on to the University of Texas at Austin with help from a Pell grant scholarship, awarded to low-income students based on financial need. He put in a few years at a prestigious Manhattan law firm and a Wall Street investment bank. Then he moved into the nonprofit world, first in Harlem, where, among other things, he worked on the project to build the first full-service supermarket there in a generation.

On Thursday, Mr. Walker, 53, will take the next step in a career that has taken him from Harlem to world-famous foundations five and a half miles away in Midtown Manhattan. He is to be named president of the Ford Foundation, the nation’s second-largest philanthropic organization. He will succeed Luis Ubiñas, who announced in March that he would step down. For Mr. Walker, the new job is a promotion. He has been a vice president at Ford since 2010, when Mr. Ubiñas hired him away from the Rockefeller Foundation, where Mr. Walker had worked for several years, also as a vice president.

Ford Foundation officials said they had hired an executive recruiting firm and conducted a wide-ranging search for a new president to manage the foundation’s $11 billion in assets and $500 million in annual grants. The search ended down the hall from Mr. Ubiñas’s office. “Darren is someone who brings high energy,” said Irene Hirano Inouye, the chairwoman of the Ford Foundation board.

He also brings a network of boldface-name friends going back to his years at the Abyssinian Development Corporation, the non-profit arm of the Abyssinian Baptist Church that played a significant role in Harlem’s resurgence. Shaun Donovan, the federal housing secretary, recalled encountering Mr. Walker when Mr. Donovan was New York City’s housing commissioner. “The thing about Darren is, he is a thinker but he is a doer in a way that there aren’t enough of in the foundation world,” Mr. Donovan said. “He gets things done.”

In an interview, Mr. Walker said the Ford Foundation had weathered the recession and was ready to focus on new issues and initiatives. He said the endowment had rebounded to roughly where it was before the recession. It sank nearly 30 percent in 2009, to $8 billion. Mr. Ubiñas responded by cutting costs by $25 million a year, partly by trimming the 550-person payroll through voluntary buyouts and by streamlining the foundation’s operations, including reducing the number of field offices and renegotiating supplier contracts.

But the nonprofit landscape has changed with time, and the 77-year-old Ford Foundation is now outspent by newer groups like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which listed assets of $36.4 billion in 2012. The Gates Foundation made grants of $3.4 billion last year and has about three times as many employees as the Ford Foundation.

“It’s not about whether Ford or Rockefeller have been eclipsed by Gates,” Mr. Walker said. “Understanding the landscape of philanthropy, which is diverse, everyone has a role to play and a contribution to make. It’s not as if there is competition and one will eclipse the other. It’s a false dichotomy because each has a role to play.”

As a vice president, Mr. Walker has supervised more than 30 percent of the Ford Foundation’s grants, covering things like educational access and reproductive rights. He was responsible for grants for “Just Films,” a documentary motion-picture fund, and for “ArtPlace,” a public-private collaboration that supports cultural development in rural America. His portfolio also included four offices that handled regional programming in Africa and the Middle East.

Before moving to the Ford Foundation, Mr. Walker spent eight years at the Rockefeller Foundation as vice president for foundation initiatives. He supervised the foundation’s foreign offices and also led its recovery program in the South after Hurricane Katrina.

He had been chief operating officer of the Abyssinian Development Corporation and was involved in the project for the Pathmark supermarket that opened on East 125th Street in 1999.

“The Pathmark was a turning point for Harlem,” Mr. Walker said. “When we first presented the idea of a supermarket, a lot of people thought we were being unrealistic and this was a pie-in-the-sky idea, even though it was based on the evidence which clearly indicated there were as many people in Upper Manhattan as there are in Atlanta and yet it was a total food desert.”

The evidence also showed that people in Harlem were spending a disproportionate amount of income on food, he said. “We would have meetings with national vendors who shall go unnamed who would say things like, ‘We wouldn’t open a bookstore in Harlem because African-Americans don’t read,’ ” Mr. Walker said. “We would hear things like that.”

article by James Barron via nytimes.com

Ford Foundation officials said they had hired an executive recruiting firm and conducted a wide-ranging search for a new president to manage the foundation’s $11 billion in assets and $500 million in annual grants. The search ended down the hall from Mr. Ubiñas’s office. “Darren is someone who brings high energy,” said Irene Hirano Inouye, the chairwoman of the Ford Foundation board.

He also brings a network of boldface-name friends going back to his years at the Abyssinian Development Corporation, the non-profit arm of the Abyssinian Baptist Church that played a significant role in Harlem’s resurgence. Shaun Donovan, the federal housing secretary, recalled encountering Mr. Walker when Mr. Donovan was New York City’s housing commissioner. “The thing about Darren is, he is a thinker but he is a doer in a way that there aren’t enough of in the foundation world,” Mr. Donovan said. “He gets things done.”

In an interview, Mr. Walker said the Ford Foundation had weathered the recession and was ready to focus on new issues and initiatives. He said the endowment had rebounded to roughly where it was before the recession. It sank nearly 30 percent in 2009, to $8 billion. Mr. Ubiñas responded by cutting costs by $25 million a year, partly by trimming the 550-person payroll through voluntary buyouts and by streamlining the foundation’s operations, including reducing the number of field offices and renegotiating supplier contracts.

But the nonprofit landscape has changed with time, and the 77-year-old Ford Foundation is now outspent by newer groups like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which listed assets of $36.4 billion in 2012. The Gates Foundation made grants of $3.4 billion last year and has about three times as many employees as the Ford Foundation.

“It’s not about whether Ford or Rockefeller have been eclipsed by Gates,” Mr. Walker said. “Understanding the landscape of philanthropy, which is diverse, everyone has a role to play and a contribution to make. It’s not as if there is competition and one will eclipse the other. It’s a false dichotomy because each has a role to play.”

As a vice president, Mr. Walker has supervised more than 30 percent of the Ford Foundation’s grants, covering things like educational access and reproductive rights. He was responsible for grants for “Just Films,” a documentary motion-picture fund, and for “ArtPlace,” a public-private collaboration that supports cultural development in rural America. His portfolio also included four offices that handled regional programming in Africa and the Middle East.

Before moving to the Ford Foundation, Mr. Walker spent eight years at the Rockefeller Foundation as vice president for foundation initiatives. He supervised the foundation’s foreign offices and also led its recovery program in the South after Hurricane Katrina.

He had been chief operating officer of the Abyssinian Development Corporation and was involved in the project for the Pathmark supermarket that opened on East 125th Street in 1999.

“The Pathmark was a turning point for Harlem,” Mr. Walker said. “When we first presented the idea of a supermarket, a lot of people thought we were being unrealistic and this was a pie-in-the-sky idea, even though it was based on the evidence which clearly indicated there were as many people in Upper Manhattan as there are in Atlanta and yet it was a total food desert.”

The evidence also showed that people in Harlem were spending a disproportionate amount of income on food, he said. “We would have meetings with national vendors who shall go unnamed who would say things like, ‘We wouldn’t open a bookstore in Harlem because African-Americans don’t read,’ ” Mr. Walker said. “We would hear things like that.”

article by James Barron via nytimes.com

[…] Darren Walker to be Named President of the Ford Foundation […]