One can help a community one is familiar with in order to make things beneficial for that community. The beauty of giving back is knowing who you are giving back to, the purpose you’re giving back and the satisfaction of realizing that the community grows based on the contribution you are making. Brian Benjamin knows this firsthand and it’s the crux of his real estate development firm, Genesis Companies.

One can help a community one is familiar with in order to make things beneficial for that community. The beauty of giving back is knowing who you are giving back to, the purpose you’re giving back and the satisfaction of realizing that the community grows based on the contribution you are making. Brian Benjamin knows this firsthand and it’s the crux of his real estate development firm, Genesis Companies.

BlackEnterprise.com was able to talk to Benjamin regarding the basis of the reason Genesis Companies has been in existence for over 10 years and growing stronger as more projects land on his plate.

BlackEnterprise:com: You are a partner in Genesis Companies could you explain to us what that is and your role in the company?

Brian Benjamin: Genesis Companies is a black-owned real estate development and construction company focused on enhancing urban communities through the development of high quality affordable and mixed-income residences in New York and New Jersey. My job is to find new development opportunities and help steer them through the predevelopment process. I also work to ensure that we have community support for our projects and that they benefit communities and improve neighborhoods.

How did you get your start in your current business?

Karim Hutson founded the company in 2004, and he was actually the first person I met on a Harvard Business School recruitment weekend when we were prospective students. He became a very good friend and so I was around Genesis since inception until I joined officially in 2010.

What gets you up in the morning to run your business?

Knowing that I am playing a role in creating quality affordable housing for residents is a great feeling. In many urban centers, like my community of Harlem, there is a lack of low-income and middle-income living opportunities, so doing something about it is challenging and rewarding.

How important, if it is important, is it to have a Black company doing business in Black communities for the benefit of Black people?

It is quite important. We primarily partner with nonprofits and churches, where trust is essential. They are giving us the power to build or renovate housing for their constituents so when they see us and communicate with us and understand that we are just like them, it puts them at ease. Furthermore, having grown up in primarily African-American communities, we understand first-hand some of the issues that our communities face due to poor quality housing, such as asthma or lack of security, and so we are very focused creating healthy and safe living environments. We know the experience of our residents, and I believe that makes us better developers.

I know this is your 10-year anniversary of Genesis, what was/is the most important thing your company has done that you are most proud of or is a high point in your 10 years?

First and foremost is surviving for 10 years through difficult economic times. It is hard work starting and growing a business in the development space. As a result, we are able to employ people and feed families, which will only grow over time. Additionally, we provided community space, at below-market rent, on the ground floor of one of our residential buildings in Harlem for a Dream Center to help underserved children and families. I recently did a site visit of the center, which is operated by First Corinthian Baptist Church, to view its progress and I was blown away by what the church is doing with the space. The amount of young people, who are impacted on a daily basis, as a result of the work we do is very gratifying.

Posts tagged as “Abyssinian Development Corporation”

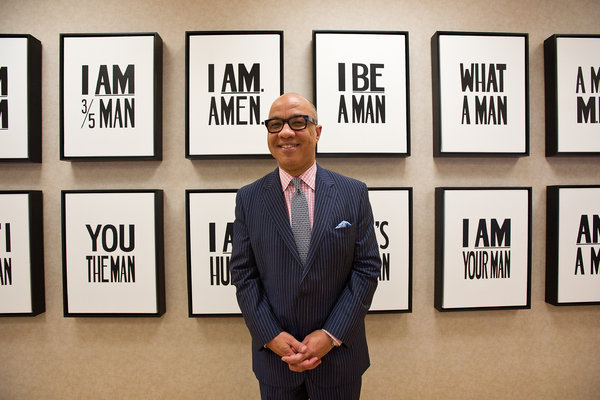

Darren Walker (pictured above) was born in a charity hospital in Lafayette, La., and grew up in the 1960s in a single-parent household in rural Texas, where his mother worked as a nurse’s aide and he was enrolled in one of the first Head Start programs. He went on to the University of Texas at Austin with help from a Pell grant scholarship, awarded to low-income students based on financial need. He put in a few years at a prestigious Manhattan law firm and a Wall Street investment bank. Then he moved into the nonprofit world, first in Harlem, where, among other things, he worked on the project to build the first full-service supermarket there in a generation.

On Thursday, Mr. Walker, 53, will take the next step in a career that has taken him from Harlem to world-famous foundations five and a half miles away in Midtown Manhattan. He is to be named president of the Ford Foundation, the nation’s second-largest philanthropic organization. He will succeed Luis Ubiñas, who announced in March that he would step down. For Mr. Walker, the new job is a promotion. He has been a vice president at Ford since 2010, when Mr. Ubiñas hired him away from the Rockefeller Foundation, where Mr. Walker had worked for several years, also as a vice president.