The “Mastry” Gallery, created by African-American artist Kerry James Marshall, walks you through Marshall’s journey of making it as a fine artist – a field dominated by whites for centuries. Marshall was born in Alabama in 1955, and as a child was a part of the last wave of The Great Migration to the west, a region still full of promise and opportunity. Marshall’s family settled in South Central Los Angeles and while growing up in Watts, Marshall pursued art and was an active participant in the movement that encouraged an increase of black artists in the art community. All of Marshall’s work contributed to his mission to prove that art by blacks was just as challenging and beautiful as the white art which was typically celebrated.

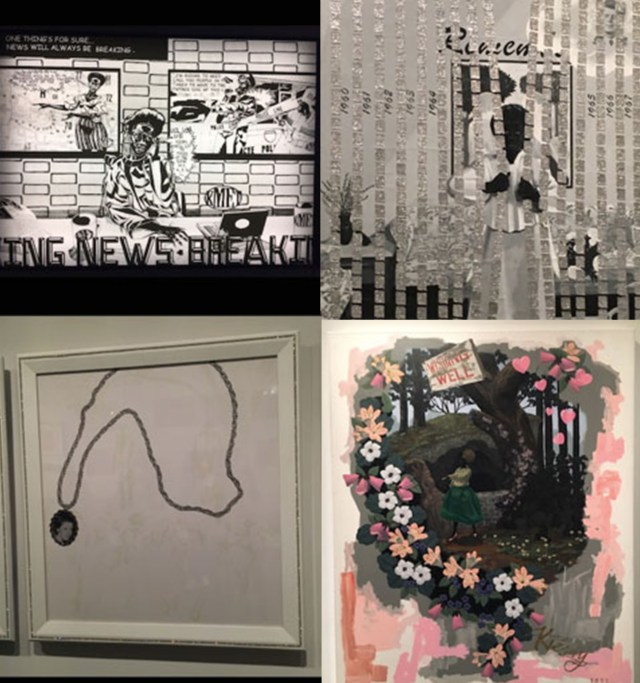

The exhibit shows Marshall’s earlier works such as “The Invisible Man,” which is a collection of small scale portraits of people using the darkest shades of black, emphasizing Marshall’s idea that black people in society blend into the background. The exhibition displays how Marshall’s work developed, and include many of his large scale paintings.

Marshall changed the style of his work because he realized that a big statement called for a grander canvas. A large three-piece work called “Heirlooms and Accessories,” appears to be a necklace with a woman’s face in it at first glance. However, once one’s eyes adjust to the painting, fine lines start to become more distinct, and it is clear that there is a lynching occurring in the background. The faces in the painting are witnesses at the lynching, and the expressions of indifference are utterly shocking. While “Heirlooms and Accessories” seem to be referring to the necklaces, accessories serves as a double meaning because it also refers to those who were accessories to murder. This is a prime example of the depth and meaning behind each of Marshall’s work.

All of the paintings reflect Marshall’s commentary on black identity in the U.S. and in traditional western art. In his piece “Harriet Tubman,” Marshall paints an image of Harriet Tubman on her wedding day, with hands with white gloves essentially hanging this piece of art in a museum. Marshall’s feeling that museums are responsible for the lack of black art is portrayed in this piece. Museums typically hold the standard of what is beautiful and worthy, and Marshall makes the direct statement of what should be celebrated in this work.

The exhibition is especially engaging because of the varying emotions each work provokes. While pieces such as “Slow Dance,” which illustrates two people peacefully dancing, provokes calmness and peace, other pieces express injustice and anger. Marshall’s versatility and innate talent for art is clear as his work consists of completely different mediums and subjects. The exhibition allows you to fully observe all of Marshall’s different forms of art and varying ideas, and is not limited to a specific time period or brand of art.

Marshall’s range of mediums and subjects include large to small scale, canvas paintings to comics, common people to historical figures, and glittery mediums to the blackest of paint. This ability to effectively utilize different forms of art makes Marshall a unique artist, and a unique person who has learned to effectively communicate in a way people of all race, gender, and social class can understand. Marshall’s works are visually stunning to say the least, and his success in spreading the meaning of his art and pursuing his career despite the circumstances of racial discrimination, is truly inspiring.

The Mastry exhibit opens on March 12 at the Museum Of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and runs through July 3.

by Lori Lakin Hutcherson, GBN Editor-in-Chief (@lakinhutcherson)

I don’t know about anyone else, but I really needed this today. I specifically set my alarm this morning to wake me at 6AM (PST) to watch Serena Williams compete for her seventh – yes, take that in – seventh Wimbledon title, and to tie Steffi Graf for the most Grand Slams won in the Open Era.

I’ll admit, regardless of the week of continued brutality and violence by police against black citizens and the gut-wrenching retaliation in Dallas because of such violence, as a lifelong fan, I most likely would have been up and watching Serena anyway. But because of its timing, this victory – this continued rising, this perseverance – was that much more coveted, and that much sweeter.

Although Williams did not mention or comment on what’s been happening in America as she accepted her trophy, don’t think she’s remained silent in the media about it. On her Twitter (which we here at GBN happily follow), she spoke directly to the recent atrocities and let us know they were on her mind days before this most crucial, career-defining match:

In London I have to wake up to this. He was black. Shot 4 times? When will something be done- no REALLY be done?!?! pic.twitter.com/OaLn60G6nm

— Serena Williams (@serenawilliams) July 7, 2016

This tweet leads me to speculate that Serena was that much more focused, that much more centered and that much more desirous of the outcome that occurred – because she knew in her heart she wasn’t just winning her 22nd Grand Slam and making history for herself, but for all of us.

![Jessica Davis (l), Tony Ramos (m), Julie Bibb Davis (r) [photo courtesy Julie Bibb Davis]](https://i0.wp.com/goodblacknews.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/fullsizerender-5.jpg?resize=405%2C296&ssl=1)